Brickfield

Brickworks and material connections

Rosanna Martin continues the story behind the creation of Brickfield for Whitegold.

The land of Trelonk, of those childhood years is off limits to me now. When my grandparents passed, the farm was sold and new ownership restricts any familial rights to it that I feel. My mum used to navigate the land by the names of the fields, telling my grandfather that she would be riding her horse up Parc n Ponds, through Kennigey, round The Mowhay and down The Gue. Gue in Cornish means enclosure, hollow or cleft. These names exist less in that land now, but have been displaced into memories, stories and our current family WhatsApp group.

Access to the clay can be still be attained from the water, and at full tide I kayaked my way along the creek in search of samples. Using my hand as a spade, I scooped out chunky handfuls and weighed down my boat. The ragworms burrowed their way through, feeding on any organic matter they could find and leaving a trace of their journeys in the blue of their wake.

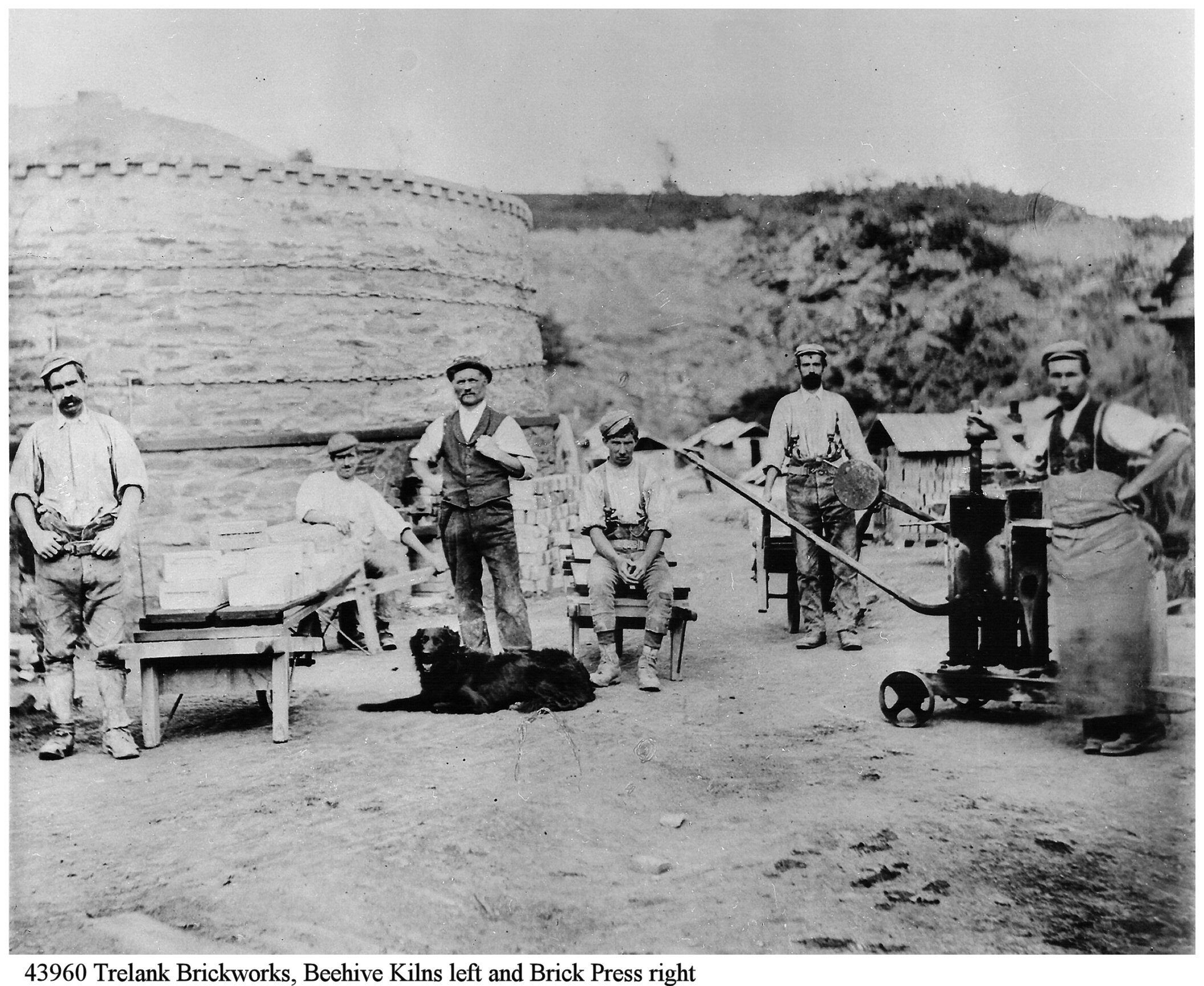

Trelonk was one of at least 70 brickworks that existed in Cornwall between the 17th to 20th Centuries. One of the first was at Trelowarren House, where clay was dug and fired on the estate and used to build parts of the house and walled gardens. Much of Cornwall’s brick and tile production was established to serve the needs of industry.

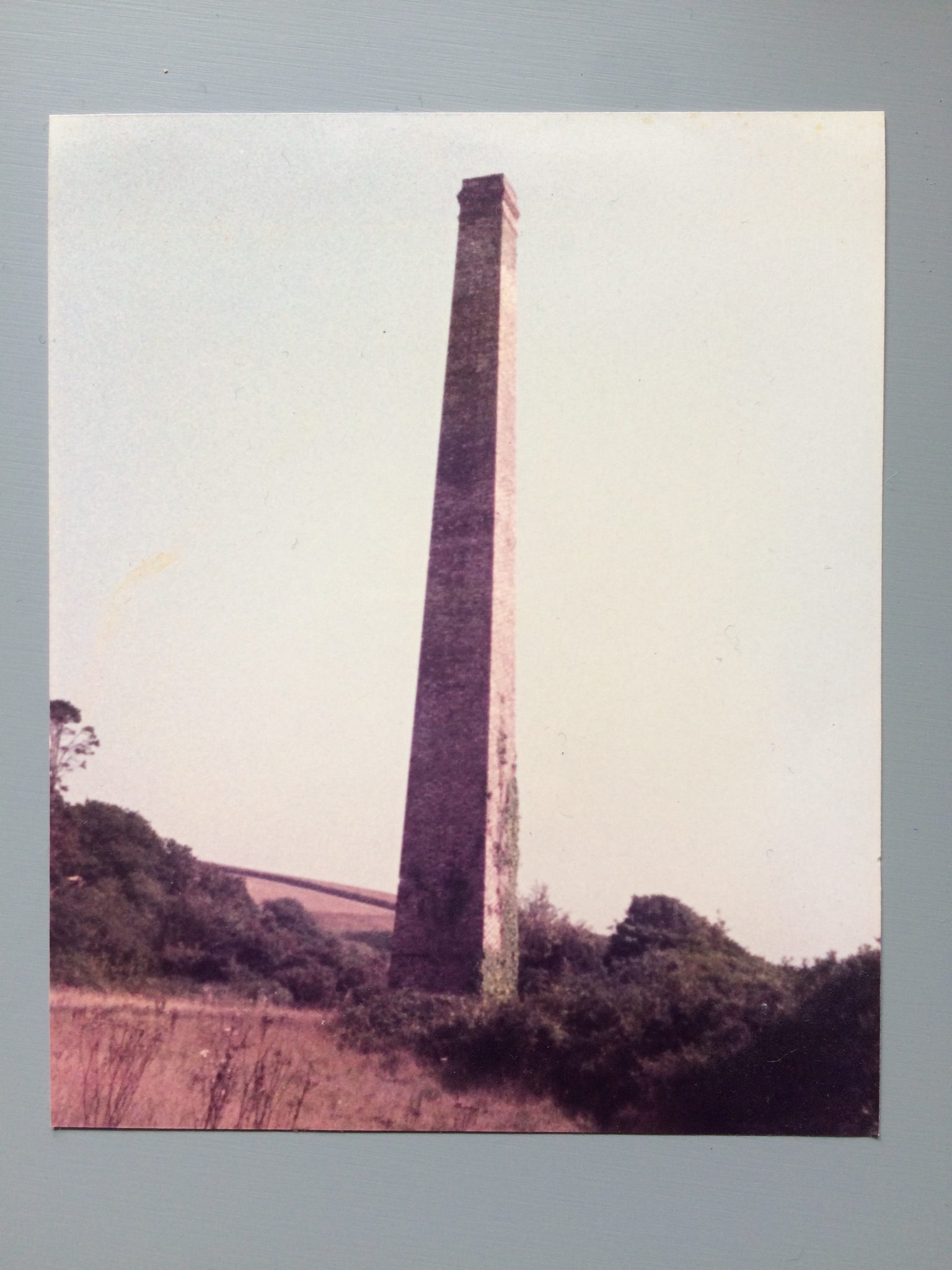

‘A particularly characteristic use was in the construction of engine house and other chimney-stacks, where brick, being lighter, was the favoured material for the topmost section.’[i]

Other brickworks were established to directly serve the china clay industry, and products were developed for specific purposes linked to the processes of extraction. China clay (kaolin) is decomposed granite. Granite is an igneous rock formed from three main constituent parts – feldspar, quartz and mica. I learnt that mica is the sparkle. Kaolin is weathered feldspar, that has broken down over many years forming tiny particles that can be washed out of the granite rock to form a slurry. The slurry is pumped up from the bottom of a quarry and needs to dry. This was done in drying sheds, using an early method of underfloor heating. Pan tiles were flat, and laid out along the base of a building with a fire underneath that gently heated the clay on top, turning it from slop to powder, ready for export.

These fragments of family history, Cornish brick making heritage, skills forgotten, and material movement got me thinking. What would it be like to try and learn from scratch the skills that were once so embedded in this place? Perhaps it came from a need to connect through making, the thing I know, with the unknown and intangible history. To deepen an understanding of a place. It started as a very personal re-finding of myself, and I wondered if it would be possible, and relevant, for others to join me on the journey.

I was invited by Teresa Gleadowe of Groundwork, programme of international art in Cornwall to run a field trip in 2018. I instantly knew I wanted to do something about the brickworks, but had never imagined it would be possible to gain access to that site. We were given special permission from the current owners to use the brickworks for a weekend in late September. Underneath the coppice my grandfather had planted, with the chimney stack looming large above us, we invited the public to join us in collecting clay from the riverbanks, to form into bricks using basic wooden frames which we then fired in a brick clamp kiln. It felt incredibly special to facilitate this weekend and we were inspired by everyone’s responses to how it felt to connect with a material directly from the land, and how by coming together, new stories were told, new perspectives of the landscapes were heard, and more and more history and myth rolled into one. I realised this landscape was not only incredibly personal to me, it was to many other people to, and we all have our own tales to tell of it.

In the months that followed, it felt pressing to build on this experience, and working alongside Katie Bunnell the idea of Brickfield was born. Through learning the skills involved in brick making, we wanted to ask questions. How do we connect to our local landscape, and the materials that are its makeup? What relevance and worth is there in learning how to hand make something that has already been industrialised? Can this connection bring fulfilment, a sense of place and connection, with both the land and each other?

‘…perhaps bricks, rather than representing walling off and protectionism, can be reminders of uniqueness, solidarity and collaboration.’[ii]

[i] Cornish Brick Making and Brick Buildings, John Ferguson and Charles Thurlow, Cornish Hillside Publications, St Austell, 2005

[ii] Clay Bricks, Essay by Fiona Hamilton in Cornerstones, Subterranean Writings, edited Mark Smalley, Little Toller Books, 2018

Share on social

---